Thursday, 17 September 2009

Monograph: Taxi Series

Monday, 14 September 2009

007 Quantum of Solace Type

Saturday, 12 September 2009

Nouvelle Vague 3 Album Sleeve

Friday, 11 September 2009

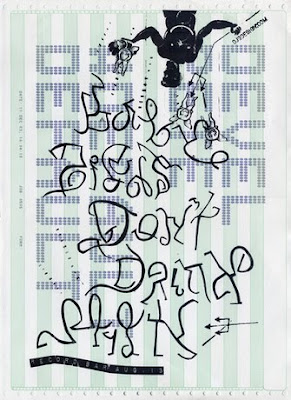

DJG Design

Mark Webber - Map Linocuts

Friday, 4 September 2009

Ink Calendar by Oscar Diaz

Ink Calendar make use of the timed pace of the ink spreading on the paper to indicate time. The ink is absorbed slowly, and the numbers in the calendar are ‘printed ‘ daily. One a day, they are filled with ink until the end of the month. The calendar enhances the perception of time passing and not only signaling it. The aim of the project is to address our senses, rather than the logical and conscious brain.

The ink colors are based on a spectrum, which relate to a “color temperature scale”, each month having a color related to our perception of the weather on that month. The colors range from dark blue in December to three shades of green in spring or orange and red in the summer.

Crit: Jeremy Leslie: What makes a magazine?

There are exceptions. The ‘surprise’ factor explains why magazines like The New Yorker and The Face remain regarded with such high esteem. But great though such titles are, they not only stick to a traditional physical format but cannot be described as typical. They are (or were in the case of The Face) exceptional for their refusal to be predictable. It is difficult to describe the New Yorker in a single sentence, its scope is so broad. Every issue contains surprises – as David Hepworth has said, “one of its chief delights is that it’s impossible to predict what’s going to be in it”. This was what made The Face great in its heyday too. It managed to combine the most unlikely parts. Political reportage sat next to fashion in a way that hadn’t been seen since earlier titles like Twen and Nova. And yes, they got things wrong: the fashion shoot based on terrorist chic springs to mind. But it was only later, when The Face became scared of making such mistakes, that it began its decline toward closure.

With the majority of magazines being nervous of straying too far from their comfort zones we need to celebrate those titles that are attempt ing to do something different. Whether mainstream or independent, consumer, b2b or customer, old or new, industry bodies like abc should be supporting innovative publications. And if we’re supporting innovation in content and presentation, why not format too? It is only relatively recently that the increased scale of magazine production has prompted so much homogeneity in physical format.

Verdana: Ikea's Flat-Pack Font

Not so long ago, in an ungainly and annoying queue at a hangar on the outskirts of town, the talk was all about great-value scented tealights. Today, the conversation has switched to fonts, and there is apoplexy. In case news hasn't reached you, Ikea has changed its global font from Futura to Verdana. This wouldn't normally raise an eyebrow, but the new catalogues have just arrived on type designers' doormats (Thud! The new Ektorp Tullsta armchair cover – only £49!), and instead of looking all industrial and tough, it now looks a little more crafted and generously rounded. It also looks less suited to a Swedish company founded on original design, and a bit more like a company you wouldn't think twice about. Online design forums are fuming, and typomaniacs are saying terrible things.

Futura has a quirkiness to it that Verdana does not, as well as a much longer history linked to a political art movement. Futura, dating from the 1920s, is loosely Constructivist (only loosely, because the proprietary version that Ikea made its own – Ikea Sans – is slightly tweaked to distinguish it from, say, something Joseph Stalin might have used). Verdana, however, is linked to something modern and frequently reviled: Microsoft. It is one of the most widely used fonts in the world, and people who care about these things dislike the way our words are becoming homogenised: the way a sign over a bank looks the same as one over a cinema; the way magazines that once looked original now look like something designed for reading online. This is what has happened with Ikea: the new look has been defined not by a company proudly parading its 66-year heritage, but by something driven by the clarity of the digital age.

Nothing wrong with that – it's a business. A new font is unlikely to have a detrimental effect on sales. (Indeed, the publicity generated by all this chatter may boost them.) But what would happen to our appreciation of the world if all our decisions were governed by commerce alone?

Futura is the most enduring work of the German designer Paul Renner. It still looks modern 82 years after its release. Verdana was designed in 1993 by Matthew Carter, a Brit now living in Boston, one of the most elegant and highly regarded type designers in the world. Carter is responsible for a great amount of the world's newsprint type; if an art editor wants a modernised newspaper masthead, they will more likely than not get Carter. I met the man recently over dinner, and he explained that Verdana was a typeface simply designed to look good on a computer screen. It was clear; it worked well in many languages; it was unambiguous even at small point sizes. (Its simplicity belies the fact that, like most typefaces, it took many months of painstaking work to perfect.)

Our awareness of different typefaces has blossomed with the pull-down menu on personal computers. "In the past," Carter says, "people who had a very well-defined sense of taste in what they wore or what they drove, didn't really have any way of expressing their taste in type. But now you can say, 'I prefer Bookman to Palatino,' and people do have feelings about it." Verdana is now the default font of choice for many who are grateful to the freedoms provided by their computers, but don't have time to consider how their work looks to others.

Which is precisely why those who do care are so upset. Verdana seems to have been chosen by Ikea by default, or at least by economics. An Ikea spokeswoman, Monika Gocic, has said that Verdana is for them because "it is more efficient and cost-effective". This is another way of saying: "We use it because everyone else does."

Should we care about these things as much as type designers do? I believe we should, and not just because in my experience type designers tend to be wise souls. If everything looked like a front page of the Times from 1950, then we may as well all still be living in black-and-white. And beyond the risk of homogeneity, there is emotion. Used well, type design defines mood, and how we think about everything we see. It can make us think seriously or frivolously; it can guide us effortlessly, or it can entertain us viscerally.

According to Swedish folklore, there are more copies of the Ikea catalogue printed each year than the Bible. It certainly has more Billy bookcases than either the Old or New Testatment, but its designers would do well to remember their history. The first movable type appeared with Gutenberg's Bible in the 1450s, and everything followed from there. In this strange way, the multi-million print-run of the Ikea catalogue has now adopted a cloak of heavy responsibility. But things could be worse. It could be in Helvetica.

- Simon Garfield's book about type design will be published by Profile Books next year

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/sep/02/ikea-verdana-font